In India’s startup ecosystem today, it’s not uncommon to find a company with no product, no revenue—but a INR 100 Cr valuation. That’s not ambition—that’s a structural risk we’re normalising. But are we setting serious founders up for success by doing this, or are we making it harder for them to justify their worth in later rounds?

As per a report 2024, nearly 20% of Indian startups that raised large rounds in 2023 have faced down rounds or flat rounds after failing to meet their projected traction.

This trend reflects a deeper issue in India’s venture capital ecosystem, where pre-seed and seed stage valuations are surging sharply—often disconnected from a startup’s current operational reality. Many early-stage companies are being priced more on .

Down rounds may not drastically affect a startup’s overall lifecycle—valuation shifts are routine, much like daily price movements in public markets. However, they do create a tough spot for founders who must justify mid-stage valuations that don’t align with their current traction.

New-age fund managers are setting high benchmarks at the seed and pre-seed stages, but when those traction numbers don’t hold up and startups move to the next funding rounds, their valuation multiples start to drop, making it harder for early-stage investors to give justifiable valuation. This cycle is affecting the entire ecosystem.

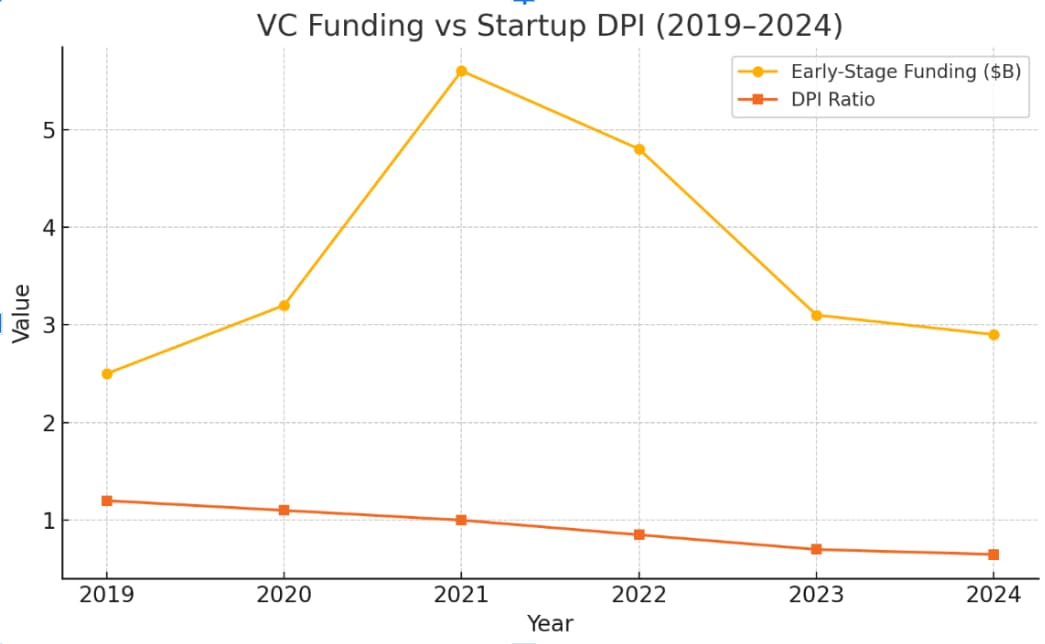

In fact, the average DPI ratio for Indian VC funds dropped from 1.2x in 2019 to just 0.7x in 2023, per an —reflecting the growing mismatch between capital invested and capital returned. Source

Source- Funding data: DPI Data:

The intent here is not to assign blame. Instead, the objective is to highlight a crucial question: Are valuations today truly reflective of a business’s real, tangible progress, or are they merely projections of future potential?

When seed stage valuations are set too high, it doesn’t just impact that one funding round—it affects the entire investment cycle.

I’m noticing that this whole situation is making investors lose interest in startups and creating challenges for serious founders in defending their valuation during subsequent funding rounds—instead of helping them succeed

One day I was talking to a foreign investor from the middle east and during the conversation he said, quote-unquote — ‘Man, you guys in India give any valuation!’ Even though deals here are done in rupees, not dollars, Indian startups are often priced as if they are already global giants.

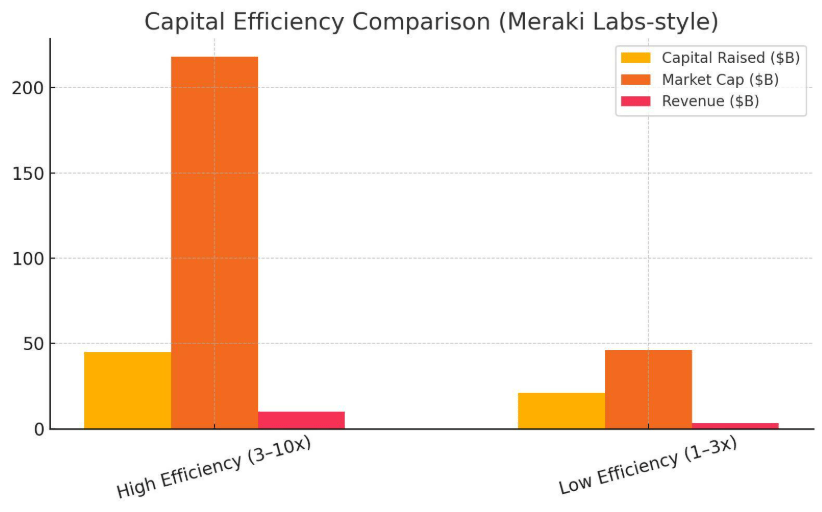

A study by Meraki Labs analysed the capital efficiency of Indian unicorns and found significant disparities. Startups with capital efficiency between 3–10x raised $45 Bn, created a market cap worth $218 Bn, and generated $10 Bn in revenues.

In contrast, those with capital efficiency between 1–3x raised $21 Bn, created a market cap worth $46 Bn, but generated only approximately $3.4 Bn in revenues, with only a handful nearing profitability.

Some companies may have gotten lucky — but luck cannot be a strategy.

In light of this, based on what they might achieve in the future, investors should focus on what they have already built and how efficiently they are using capital.

For example, if a startup has raised funds and increased its MRR from INR 10 Lakh to INR 80 Lakh per month with a reasonable valuation multiple, that makes sense. But when companies raise huge sums before even launching a product, it raises questions.

A similar trajectory was seen in the case of Koo, India’s answer to Twitter, which raised capital at a valuation of over $275 Mn. Despite initial user traction, the company struggled to monetise and shut operations in mid-2024. It’s an example of how early-stage excitement can mask fundamental business model gaps.

Some might argue that high early-stage valuations are a bet on long-term vision—and in some deep-tech or R&D-heavy industries, that holds true. But when consumer internet platforms without moats raise at 100x multiples, it’s no longer vision—it’s wishful thinking.

Of course, some companies—especially those creating entirely new industries or investing heavily in R&D — do require significant upfront capital. We even have such examples in our own portfolio at WRC. But for most businesses, valuations should be grounded in actual progress, not just projected potential.

This lack of sensitivity to valuations creates a ripple effect—each round gets priced higher, and by the time later-stage investors step in, either the founder has to do a down round or the growth potential doesn’t justify the price. As a result, returns are shrinking, and interest in the asset class is declining and reconsidering fresh allocations.

You might be able to recall the statement, “Most (Indian) startups were too richly valued and SoftBank could not justify those valuations,” said a report.

That’s why the conversation needs to shift from what might happen to what startups have already built and how efficiently founders are using capital.

At the end of the day, sustainable investing is about ensuring that every round of funding sets the company up for long-term success—not just securing the next step at a higher price. If we don’t address this now, we risk turning venture capital into a less appealing asset class, where inflated valuations lead to disappointing returns.

It’s time to realign incentives and bring back rationality in early-stage investing. The next time you see a INR 40 Cr valuation on a startup that hasn’t shipped a product—ask not what it might become, but what it has already done. That one question might just save your portfolio.

The post appeared first on .

You may also like

UNSC to discuss rising India-Pakistan tensions after Pahalgam terror attack

The Log9 Collapse, Swiggy Bottles Genie & More

Beyond Chatbots: The Power of Agentic AI In CX Automation

Spain's best seaside city named and you can fly there for just £50

Start the week with a film: 'Groundhog Day' is about a time loop we don't want to escape